We don’t go next door to borrow a cup of sugar very often. Does this lead to community isolation?

Here’s a great illustrated story from YES magazine.

The story starts here….. Continue Reading

We don’t go next door to borrow a cup of sugar very often. Does this lead to community isolation?

Here’s a great illustrated story from YES magazine.

The story starts here….. Continue Reading

When we talk about infrastructure we are usually talking about things like roads and water pipes. But communities also need to be concerned about their “civic infrastructure.” A recent article by University of San Diego professor Keith Pezzoli defines civic infrastructure as “formal and informal institutional as well as sociocultural means of connectivity used in knowledge–action collaboration and networking.”

The William Penn Foundation suggests the concept of civic infrastructure links social and cultural capital in communities with built capital, in that public spaces in communities also can be understood to be an integral component of bringing people together and creating the kind of capacity for collective action that is what civic infrastructure is all about. A recent report by the foundation argues that “Civic infrastructure encompasses the physical spaces, buildings, and assets themselves, as well as the habits, traditions, management, and other social, political, and cultural processes that bring them to life—two realms that, together, constitute a whole.”

Building civic infrastructure requires a multi-pronged approach. It involves placing greater emphasis on public or civic spaces. It involves creating meaningful opportunities for civic dialogue and learning to take place. It involves creating opportunities for public work. It involves investing in civic institutions and efforts to build a strong community culture. It certainly involves work across the public, private, and non-for-profit sectors.

One way local governments have been working to build civic infrastructure is through offering citizens academies. Continue Reading

The Great Recession and crisis of 2007-2010 raised questions about whether low and moderate-income families should be home owners, given the financial risk, or would be better off as renters. Beyond the financial arguments about property investment and equity is the question of other potential benefits in being a homeowner.

I’m glad to point readers to research by UNC-Chapel Hill’s Dr. Roberto Quercia, and his colleagues Kim Manturuk and Mark R. Lindblad, in their new book A Place Called Home: The Social Dimensions of Homeownership. They found that homeownership has important non-financial benefits for low- and moderate-income people.

In past blog posts those of us in higher education have focused on issues related to disseminating research findings and working in partnership with community groups. In this post I want to raise another issue – one that focuses on our teaching mission.

While it often seems that the primary purpose of higher education has become only job preparation, there is another movement afoot that focuses on restoring the civic mission of higher education. When the first universities, both public and private, were established in the early days of the republic, a significant emphasis was on preparing students for life in a democratic society.

The question I’d like to discuss today is what it is institutions of higher education, whether they be community colleges or four year institutions, should be doing to prepare their students to be engaged citizens after the graduate? What skills, habits, and dispositions would those of us living in these communities want them to have and how might we best teach this?

Engagement and commitment are intangibles; they come from within. It’s the culmination of the psychological, social and intellectual connection one has with matters that affect their communities.

This connection is what motivates and is ultimately the driving force behind productive, progressive change. Giving people freedom to make decisions engages and empowers them and within the local community this has to occur through mutual respect, caring and group participation. The process of empowerment does not happen alone; it’s accomplished with others. So as citizens collectively engage, change becomes a part of the culture rather than temporary solutions to permanent problems.

Active community engagement represents a certain optimism that one’s effort and dedication can and will improve the social and economic infrastructure necessary for communal stability. Continue Reading

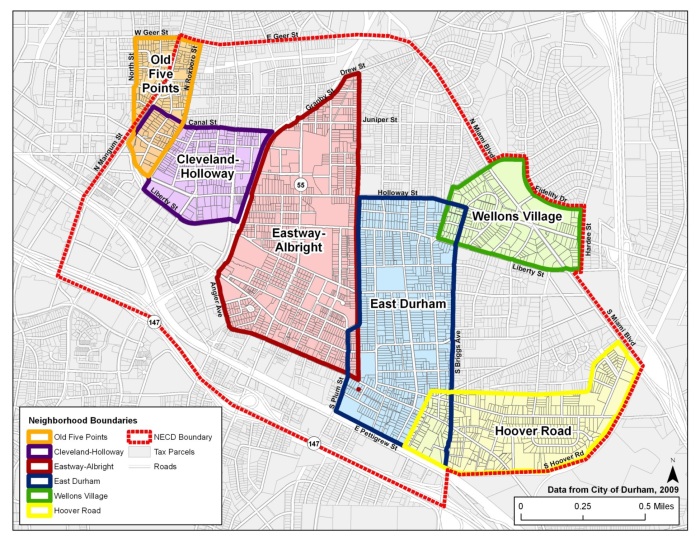

Durham Mayor Bill Bell announced an anti-poverty initiative in early 2014, and then focused some of it on Northeast Central neighborhoods (per the map above)

http://www.heraldsun.com/news/x2025289216/North-East-Central-Durham-target-of-poverty-fight

The section of North-East Central Durham (NECD) the mayor is targeting is home to about 3,466 people. It has a 61.4 percent poverty rate, with annual incomes there averaging $10,005 per person. Mayor Bell suggested organizing community members and leaders into task forces to gather information about any shortcomings in education, health care, employment, housing and public safety in the target area. Bell wants all of Durham’s key governmental, education, business and nonprofit institutions to play a part.

Here are some ideas shared by me and some residents in the neighborhoods about how to organize the work to reduce poverty in the targeted area.

This strategy focuses on making sure recommendations address the current and projected needs of existing residents. While it is important to attract additional residents into the neighborhood to improve income base strength, the plan is sensitive to minimize resident displacement and target solutions needed to meet the needs of the current residents.

This is about community engagement at its core, with the community being a full partner. The process worked at the start, even if it wasn’t sustained.

Getting Started:

The Northeast Central Durham Partners Against Crime (NECD) started with 8 Durham neighborhoods; Edgemont, Hyde Park, Albright, East End, Hoover Road, Y.E. Smith, Wellon Village and Sherwood Park. The driving force behind NECD was Calina Smith & Willard Perry, from the Community, Carl Washington, the City’s liaison to NECD, and Michael Page, the County’s Human Services Coordinator. As conversations began in the neighborhoods, most of the leaders along with Chief Jackie McNeil bought into the Weed & Seed Concept; which was that Law enforcement would help weed those neighborhoods of most of the criminal’s elements in the area & the City & County along with the neighborhoods would sow seeds of prosperity. Continue Reading

Citizens academies are educational programs conducted by cities and counties aiming to create better informed and engaged citizens. These programs involve ordinary citizens participating in several (usually between six and twelve) sessions taught by local government officials on the wide range of local government services and operations. Programs are usually taught to cohorts of 20-25 residents and end with a graduation. Participants not only learn about their local government, but also learn about how they can be directly involved in it by, for example, serving on citizen advisory boards or committees. Continue Reading