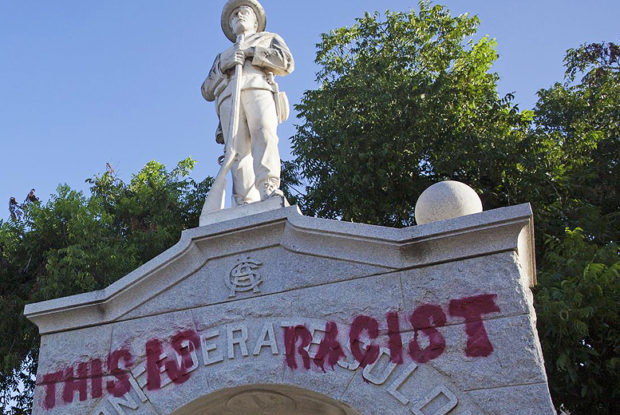

Five months after the Charlottesville rally and protest, the debate over what to do with numerous Confederate statues which pepper much of the South remains as strong – and as polarized – as ever before.

Just days after the massive protests and violence in the Virginia city, four Confederate monuments in Baltimore and three on the campus of the University of Texas, Austin were taken down by city authorities, with another in Durham toppled by protesters. In October, the scene was repeated in Lexington, Kentucky. Last month, two statues were removed in Memphis, while the infamous “Johnny Reb” statue expelled from an Orlando park in June was transferred to a city-owned cemetery. Finally, this month saw the Virginia legislature debate letting the state’s localities decide what to do with public Confederate symbols, while dueling bills promise to heighten Missouri’s dispute on tributes to former Confederate soldiers.

Back in August, John Stephens contributed a great post on this topic. In it, he skipped the contentious question of what to do with the statues – many of which are intimidating Jim Crow-era odes to men who were proud upholders of racial hierarchies – and focused on the how: how cities, counties, and other local jurisdictions should engage all segments of the public in a structured manner to come to a resolution that works best for their communities. Indeed, there is already evidence that Louisville; Atlanta; Denton, TX; and a few other local governments are doing this to some degree in relation to their Confederate monuments.

I argue that when it comes to historical structures that are the root of community tension, the answer should almost never be to physically remove them.

First, removing or even moving a Confederate statue in response to angry citizens sets up a zero-sum encounter, where it is clear that one group “wins” while the other “loses.” These situations often serve to harden beliefs on both sides and raise tension. While there are examples of zero-sum games in local government – think of the hunt for limited state and federal grants – much of modern economic and psychological scholarship focuses on ways to “expand the pie” and come up with solutions where one side’s gain is not necessarily the other side’s loss. As John mentioned, one substitute for doing away with a controversial monument is building another to a more inclusive person or idea in an equally public location. Moreover, a negotiated solution could even include non-physical substitutes, such as increased funding for minority scholarships or a public commitment to make local government hiring more diverse.

What is also troublesome about toppling such symbols is the slippery slope that may follow. Here are some challenges I see about how community conversations could proceed that would make it harder for people to come together and manage their differences.

While most would argue that there is a moral distinction between, say, Jefferson Davis and Thomas Jefferson, if these prominent leaders are judged by modern sensibilities, both would be seen as morally repugnant for owning slaves. Should the University of Virginia or the University of Missouri remove their monuments to our nation’s third president? If so, what of statues of or memorials to George Washington, James Madison, and other slave-owning Founding Fathers? If you answered “yes” to both of these questions – perhaps because being a slaveowner is the line you draw in the sand – what of overtly racist beliefs? Few realize that even Mahatma Gandhi, while he was in South Africa, routinely expressed “disdain” for black Africans, describing them as “savage,” “raw,” and living a life of “indolence and nakedness” in his early writings. Numerous American cities proudly exhibit Gandhi statues. Should they go as well?

Much of this has to do with how we tend to deify our “heroes” and reprove our “villains.” Numerous psychological studies show that humans are “simplicity-seeking” creatures because, evolutionarily speaking, a lack of nuance helped our species survive thousands of years ago. But it’s precisely this lack of nuance which is at the root of our country’s historically-high levels of political polarization. That’s why it’s so hard for us to realize that, say, not everything that Mother Theresa did was unequivocally wonderful. Similarly, not everything espoused by those of a different political ideology is rooted in oppression and bigotry.

Finally, symbols to honor historic figures mean different things to different people. A proposal for a new statue, or to remove a statute sparks discussion in a way that a typical high school social studies course or a historical documentary can’t. It’s through this discussion, for instance, that a black resident might learn that nearly a quarter of Southern white men in their twenties died through conflict or disease as a result of the Civil War. Or, for example, that a white resident might understand Jim Crow led to situations such as what befell black voters in Louisiana, who precipitously dropped from more than 130,000 registered voters in 1896 to one percent of that number just eight years later. A respectful, productive discussion obviously is not a given (especially due to our present tendency to talk over each other rather than productively engage), but can be encouraged through plaques, more robust history curricula, and cooperation among faith leaders.

Iconoclasm – or the political belief in the importance of destroying certain icons or monuments – is tempting, especially when the targets – Confederate statues – serve as daily reminders of government repression among some of its victims. Civic engagement initiatives can serve an essential purpose in bridging this divide between citizens. However, without limits, the outcome may prove to be even more unhealthy for community members and governments both.

To add to this thread; Richmond VA has a mayor’s initiated citizen commission examining its confederate statuary. Here is news from May 2018 about one public gathering with various ways that the audience participated: http://www.richmond.com/news/local/city-of-richmond/monument-avenue-commission-convenes-as-it-prepares-to-wind-down/article_6b8716ba-3122-5de3-8169-41e29cb0d64b.html And here is more details about the Monument Avenue Commission: https://www.monumentavenuecommission.org/#home-section

Thanks, John. Yeah, it seems that Richmond is among the cities to watch in terms of how much they are striving to offer all citizens an opportunity to comment – and ultimately decide on – the statues. My article takes more of a long-term view, one that takes into account the negative of taking down the statues years down the line, even in the face of massive public opposition to them. My fear is that even if a deliberative, highly engaging process resulted in a city removing them from view, it promotes a simplistic, black-white view of history that will only hurt us in the long term. How that squares with the need to make local government more engaging and participative for citizens, I’m not sure…

Also, how about the statue of Abraham Lincoln that some people in Boston want to be torn down because it also depicts EMANCIPATED slave with Lincoln, how is that racist?! It appears that some people do not want statues of any whites associated with history, no matter their role, but in the same city, the mayor apposed renaming a facility that was named for a black slave owner and that facility is located where the black slave market was at! How racist is that!

Since slavery was both legal and widely accepted in the early years of our country, some forgiveness should be granted to luminaries of the time, especially those who eventually freed their slaves and/or laid the groundwork for others to do likewise. Statues of or memorials to George Washington, James Madison, Thomas Jefferson and other slave-owning Founding Fathers should remain, as well as U.S. Grant, who was instrumental in winning the war to end slavery, even tho he reluctantly accepted one slave for a while earlier in his life, before freeing him.

The traitors who fought against the USA deserve to have their statues removed, or at the least, have a scarlet R (for racism) on their chest.

Thanks for sharing, Sharon. My views on this topic have evolved in the nearly three years since writing this post. But I continue to struggle with this question: how to balance the very real effects of historically racialized systems with the symbols of that era which mean very different things to very different people.

Thanks, Mark. That’s a more nuanced way to differentiate between what should be torn down and what should stay that I’ve heard from some friends too. I think I can get behind that. The question that will always be asked, though, is where is the line drawn? Since even among non-Confederates, one person’s luminary may be reviled by others. To me, that’s the ultimate issue with tearing down historical symbols. It’s incredibly hard to not put on a somewhat modern lens when judging those figures. That’s why I sometimes lean towards keeping them all, but making it super clear when the figure was a racist, or a national hero who also did some despicable things. And at the same time, building up a lot more statues of Black, Latino, and other national figures who aren’t as stained by the Confederacy, slavery, racism, and prejudice.