I recently was asked to speak to a joint meeting of town councils of four communities in Eastern North Carolina. The subject they asked me to speak about was community engagement. What I ended up spending most of my time talking about were two frames for thinking about the role of local government in the overall process of community building. The two frames are local government as vending machine and local government as barn raising. In 1996, Frank Benest, former city manager of Palo Alto, California, wrote an article in ICMA’s Public Management (PM) magazine asking whether local government was serving customers or engaging citizens. He used the metaphor of the vending machine (which he attributed to another city manager, Rick Cole) to describe the common way local government’s are thought of.

Benest writes, “The vending machine is somewhat mysterious: people do not know precisely how it works. They drop in 25 cents in taxes or fees and expect the machine to dispense at least 25 cents in services. When the machine does not work to everyone’s expectations, people start cussing at it and kicking it. Sound familiar?” Under this transactional model, local government is (at best) on the periphery of community building. It is a resource residents use, not unlike a gas station or grocery store. Benest points out that such a model views citizens as passive consumers, with no particular allegiance to their government, or to each other for that matter.

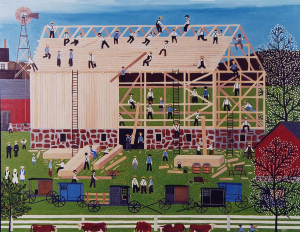

A better metaphor, argues Benest, would be a barn raising that is common in Amish communities. This image, utilized by Daniel Kemmis in his classic book Community and the Politics of Place, views government as a partner in community building. According to Benest, “The barn-raising approach promotes citizen responsibility as opposed to the passive consumption of services. When confronted with a problem, people do not ask, “What is government going to do for us?” Rather, they focus on “What are we going to do?”

Benest was writing in the 1990s and really was at the leading edge of thought when it comes to this question of local government role in community building. As time has gone on, the barn raising model has become more widely embraced by local government managers and local elected leaders alike. For example, the International City/County Management Association (ICMA) has promoted a strong barn-raising, community building model for practice for some time now. The extensive report titled “Connected Communities: Local Governments as a Partner in Citizen Engagement and Community Building,” published in 2010, captures this perspective well. Similarly, the National League of Cities has for over a decade now strongly embraced civic engagement. For example, consider this language from the NLC website: “Broad participation by residents in government and public life strengthens democracy and governance at the local level, resulting in a more informed and inclusive community built on trust that can more effectively meet the needs of all stakeholders.”

But the barn raising frame is not universal. The transactional, vending machine model still persists in (at least) American culture. Rhetoric that pits citizens against government, an us-them mentality, is still popular as evidenced in op-ed pages of local newspapers or grousing threads on social media.

Yet when you closely examine resilient communities, places that seem to have a collective growth mindset, places that people like to call “home,” what you will find is more of a barn-raising culture. Strong communities are less us-them and more “we the people.” Such communities are not without their problems; it’s just that they approach their problems from a barn-raising perspective, one that is transformational as opposed to transactional. Local government is not only an integral institution of the community, it embodies, expresses, and elevates community.

Could it be that a primary factor separating resilient, vibrant communities from those that are in decline is the civic culture, and by extension, the way that culture views local government and the way local governments view themselves? I think so. Certainly there are other macro-factors involved. Of course the reality is less binary, as there may be aspects of both perspectives active in any given place. But I do think the metaphors employed by Benest, contrasting these two perspectives, offer a helpful way to think about the role of local government in community building and civic engagement. I think it provides a great question for residents and local government leaders alike to ask themselves. Which image best describes our local government? A vending machine? Or a barn raising?

This post can also be found on the Community and Economic Development in North Carolina and Beyond blog.

Rick – I like many parts of how you think the barn raising model may be the best fit for local government leaders envisioning their role in community development.

A couple of challenges for your thinking:

a) Who gets served? Per barn raising as something that works in a stable, tightly-knit community (you cited Amish practices) seems quite different from the splits in many communities, and different perceptions of need and fairness in community development. Other blog authors have cited neglect of neighborhoods and challenges of revitalization without supporting private sector and public sector actions which result in gentrification and further disadvantage for low-income residents.

For example, contributor Stephen Hopkins wrote: The problem I see now is that with all of these good things happening in Durham, not many poor blacks are benefiting, in fact we are being forced out of our neighborhoods, and young blacks men and women aren’t getting the good paying jobs and the black owned businesses are dying out. https://cele.sog.unc.edu/when-progress-is-at-odds/

So, how do you address this apparent weakness of the barn-raising model?

b) Opportunity to participate: many standard forms of participation – e.g. public hearings, government-created advisory boards – tend to draw unequally from different neighborhoods or groups and sets of interest in the community. Whereas the barn raising metaphor is focused on a short-term effort, with a strong sense of mutuality (and reciprocity – I work on your barn now, I can expect your help later), I do not see how this applies to the rules on funding of community development projects and mainly impersonal forms of accountability which guide local government’s role in grants; tax abatements; help on streets, water and sewer service, etc.

Fair points John, though I believe the contrasting metaphors are not so much at the level of specific strategies and more at the level of perspectives. Thus I think the transactional “vending machine” approach lends itself to in-groups and out-groups (I’m getting what I want out of the machine versus I am not getting what I want out of it) whereas the barn raising, transformational approach inherently thinks in terms of the whole community, and everyone coming together to improve the community as a whole. Thus if there are pockets of the community in decline, the natural response would be for the whole community to come together to lift that up (raise a barn in that neighborhood, if you will) as opposed to thinking transactionally in terms of making sure dollars going in equate with services going out (an accounting that doesn’t work when you are talking about alleviating poverty or overcoming other historical disparities). So I’d say that one framework or philosophy is better than another for approaching community development. But the specifics on the ground are more complex than just one lens or another, of course. I would say though that in terms of community development, the vending machine model seems to fit the deficits-based, outside-in approach, while the barn raising model reflects an assets-based, inside-out approach.

Local government as barn raising! I love it! I’ve often thought that one of the best things towns and cities can do to improve their livability and loveability is to welcome engagement and investment from their citizens. Make it easy for a citizen with a good idea to make something interesting happen in your town! But a lot of local governments haven’t figured out how to do that. They’re remain inaccessible, opaque, and bound up in red tape and cultural traditions. Next column: examples of how communities create a barn-raising model for themselves.

To somewhat echo what John mentioned, my fear is that this dichotomy is either caused by our deeply-held culture of individualism in the US, or the deeply-held divisions in our community whose fault lines are often based on race and ethnicity. In this view, “vending machines” or “barn raisings” are symptoms that local governments have less ability to address. I would love to be proved wrong by empirical data, but from experience and studies I’ve perused, I think some of the best examples of community-led engagement initiatives have come from relatively culturally homogenous areas, like direct democracy in New England small towns or successful campaigns against food deserts in majority-Black neighborhoods in Greensboro, Oakland, and elsewhere. I used to work on the budget engagement side, and so I have seen examples counter to this in Hartford, San Antonio, and a few other cities, where municipal administrations make a real attempt to garner budget-related feedback from minority areas of their city, and (sometimes) incorporate this feedback into their city budget. But, sadly, efforts like this are few and far between, and even when they work, I would argue that they’re only addressing the low-hanging fruit of civic engagement. Still, I would love to be shown otherwise…