As we’re constantly told, this is The Age of Big Data, and tapping into that monstrous yet murky term indeed has the potential to revolutionize the way organizations function, particularly when it comes to finances. Local government and other public entities are no exception.

Indeed, many are increasingly publishing reams of financial data, like procurement contracts, salaries, and details of their various budgets. Some of this is still done in old-fashioned ways – many of us know how frustrating it is to mine data from PDFs of scanned documents, for instance. Yet even when Big Data is made available by governments in a standard format, with accompanying APIs for coders to freely draw from, and with aesthetically pleasing visualizations, is that enough?

No, that is not nearly enough.

What is financial transparency?

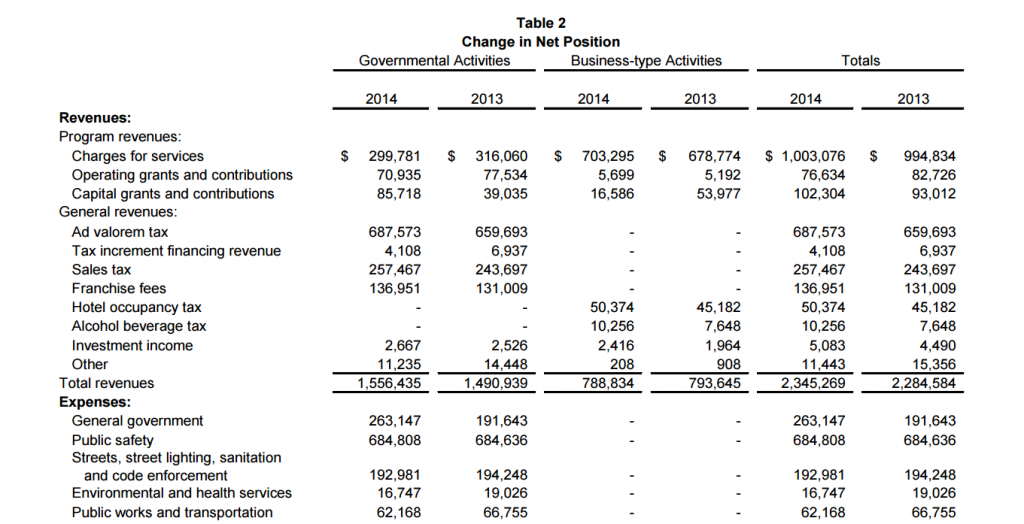

At its core, financial transparency is about disclosure: making sure that an entity’s books are open and, ideally, searchable. This, in theory, promotes public accountability of taxpayer money. While some would argue that the current legal financial disclosure framework (case in point: the dreaded Comprehensive Annual Financial Report [CAFR]) is sufficient, it is largely comprised of a web of documents that are created by accountants, intended for other accountants, and okayed by auditors (who are also accountants) following guidelines from an organization with perhaps the least exciting name ever: the Governmental Accounting Standards Board. A typical CAFR begins with a table of contents listing the names of funds as diverse as the Supplemental Environmental Project Fund and the Digital Automated Red Light Enforcement Program Fund, and continues with, literally, hundreds of tables detailing yearly assets, liabilities, and cash flows (think of your high school financial planning class, just with a million times more detail).

“Financial transparency” 1.0

This is difficult stuff for even CPAs to grasp, let alone average citizens whose tax dollars are being described in such granular detail.

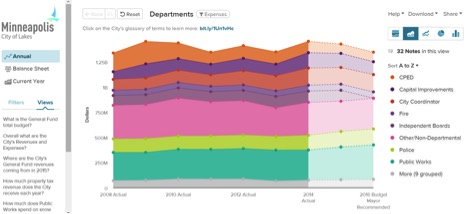

What of when this financial data is converted into clickable tables and charts? Now we’re getting somewhere. Most current financial transparency efforts focus on this: converting a public entity’s balance sheet into interactive, colorful graphs. This is a big step forward, allowing residents to more easily navigate a responsive, well-designed website in search of the answers to such questions as “How much property tax revenue does my school district receive every year?” or “How does my city’s current year Parks and Rec spending compare to that of previous years?”

A more recent, interactive financial transparency website

Yet, play around with a typical financial transparency portal and you’ll eventually realize two things: 1) the information is still kind of overwhelming, and 2) there’s no actual place for citizen feedback.

In short, for all the sexy graphs and interactive web design, residents of most public entities across the world still don’t have meaningful opportunities to UNDERSTAND and PARTICIPATE IN budget processes. What’s missing is civic engagement.

Enter engagement

Civic/public engagement means getting community members involved in the decisions that affect their daily lives. It’s not a replacement for representative democracy – people shouldn’t be expected to vote on every decision a public entity makes – but it’s an invaluable complement to it, promoting trust, leading to more effective and equitable outcomes for all population groups, and helping to develop the next generation of local leaders.

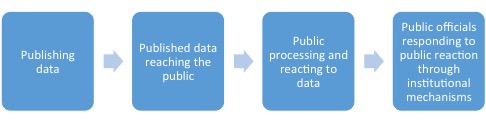

World Bank digital engagement scholar Tiago Peixoto has written at length about the difference between transparency and actual public participation/civic engagement and illustrates it nicely with a simple four-step accountability cycle:

Even in the best case scenario, where open data initiatives are well-publicized and covered by the media, fiscal transparency only covers one-half of the accountability cycle. The rest is down to civic engagement efforts and official mechanisms for translating them into concrete action.

Building engagement on a foundation of fiscal transparency

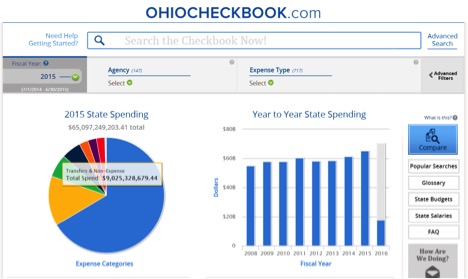

What’s actually needed to get citizens involved with government and to work hand-in-hand to solve shared problems, particularly around the budget? There’s no magic bullet or killer app. Publishing financial information in an easily digestible manner is certainly a prerequisite, and I applaud civic technology companies for making this step easier for public entities. A great example of a potentially game-changing fiscal transparency effort is the State of Ohio’s “Open Checkbook” platform which will soon list everything from departmental travel expenses to sick leave compensation from schools, villages, towns, cities, and counties across the Buckeye State. This type of more accessible financial information is not just useful for residents, but for public employees too, who often have as difficult a time processing nearly-indecipherable data tables.

Some examples of data visualizations on OhioCheckbook.com

But real civic engagement often also takes a bit of creativity, not to mention a willingness to move past one-way information platforms into two-way feedback mechanisms. It frequently happens early, well before a certain decision is to be made, or months before a budget has to be submitted. It is sometimes done through well-organized public meetings, occasionally with the help of online tools that spur on discussion, and every so often with a blend of both (which I very much recommend). Finally, meaningful civic engagement has to entail more than just lip service from public officials, and should be coupled with clear, equally meaningful processes by which people’s voices and budget priorities are translated into concrete actions.

To make the difference even clearer, here’s my attempt at a simple table illustrating the various features of financial transparency and budget-related civic engagement.

| Shows budget details | Displays nice financial visualizations | Makes info easy-to-understand | Allows for citizens to give feedback and public officials to compile it | |

| Financial Transparency | X | X | ||

| Civic Engagement | X | X |

Did I get it right?

Are the two more similar than I make them out to be?

Or is the gulf between financial transparency and engagement even wider? Let me know!

Excellent post, Kevin!

Obviously I agree with the main points. My post here a few weeks ago (http://cele.sog.unc.edu/beautiful-budgets-opportunities-and-gaps-in-online-local-budget-engagement/) echoes the theme, that open budgets are more about presentation (transparency) than process (engagement), but your post goes into that much more deeply.

One of the most interesting points for me here is in the final table, where “Makes info easy-to-understand” is identified with engagement and not transparency. On one hand, there absolutely should be an X on the transparency row. We tend to think that “visualization=easy-to-understand” and that’s not necessarily true. Melody Warnick’s comment on my post suggesting simple explanations of common technical terms is one obvious step, but I believe there is much more that can be done there.

At the same time, I love the idea that the best way to make things easier to understand is to engage people in the process. I think that’s one of the strengths of participatory budgeting, for example: it allows people to really grasp some of the complexity of the issues in ways that they can’t if they come at it as pure information consumers. Would love to see more expansion on this idea.

Thanks for the comment, Eric! Let me start off by saying that I’m a huge fan of CommunityBudgets.org. While with Engaged Public (makers of Balancing Act), we checked out your guys’ work quite often and loved it. And you’re spot on when you write that we have a long way to go when it comes to open budgets.

Absolutely. Whether a city is working with OpenGov or a smaller vendor, financial transparency efforts are getting more sophisticated. Sometimes, this sophistication leads to ever more layers of detail for users to click on, and ever more tables and sidebars that appear as a result. For some people, these sorts of complex, layered visualizations are quite easy to understand. But based on discussions we’ve had with community members as well as the appointed and elected officials who are tasked with interacting with them on budgets, many of these applications need to be simplified (but, key difference, not dumbed down) in order to foster greater understanding.

I’m not sure where exactly the balance lies. With Balancing Act, we wanted to limit what the user could observe and interact with to the operational/general fund, keep the number of spending/revenue categories/subcategories relatively limited, and try to encourage clients to put the important but often lengthy explanatory detail into our third layer of pop-ups (so as not to immediately overwhelm users). Some liked it, but we also got criticism from public officials that we were overly simplifying the budget process, and couldn’t quite adequately express what spending/tax boosts and cuts ACTUALLY MEAN. Others thought that we could streamline the interface and functionality even further, perhaps along the multiple choice lines of OpenNorth and Delib. The “right” answer will probably depend on the type of jurisdiction/population, and how the online tool will be supported by offline means.

I can’t agree more. Getting people involved in the process from the very early stages (particularly those who are typically underrepresented in the budget process is essential. But this, too, depends on a host of factors, and brings up a number of questions. How willing is the public entity to actually make substantial changes to the proposed budget based on public feedback? If not very, then only having the trappings of the process and not more substance can very easily turn citizens off (I love PB, but this is one of my concerns – that a ton of time and energy is spent on only a miniscule fraction of the budget, at least in most current iterations). What is the baseline level of engagement in the community, and are all channels created equally in terms of influencing decisionmakers (i.e. social media vs. in-person meetings vs. budget apps vs. “Open Town Hall”-type of apps)? Does this entire process ultimately lead to direct democracy and undermine representative democracy?

Sorry for the thesis – I’d love to hear more of your thoughts!

Would love to have a more in-depth conversation at some point … there are so many layers to this!

It strikes me that part of the problem with defining the right level of detail lies in trying to find a single solution for multiple constituencies. Creating a budget tool for “citizens” is about as useful as creating an online product for “web users”. In some cases a tool or process is most useful for engaging proxies for citizens (media, advocacy groups, etc.), in others there is an opportunity to engage more directly with a group of citizens who share a particular interest. One of the biggest dangers is what you note in your response to Emily’s comment – that officials will conflate some particular piece of a piece of a solution for the whole thing.

I will think more on what you’ve said here and, hopefully, incorporate some of the results in my follow-up post next month.

Well said. I wish I knew what the balance is between creating apps that “templatize” certain processes and visualizations to foster adoption vs. having a multiplicity of platforms that are uniquely customized for each type of locality/constituency. Still searching for that secret sauce!

I’m looking forward to your upcoming post.

LOVE this post, thank you so much for following up on Eric’s post of a few weeks ago. There is such a gap between participatory and presentational strategies, yet no one really discusses those. That assumption – that if you put it out there and make it “sexy,” it counts – has done a lot of damage to public desires to participate in any budgeting process at all. Yet it is the foundational component of what their public servants provide for them.

I wish I had more time to discuss this with you both, but wanted to make sure you knew that these posts were relevant and important! Sharing out to my own networks as well.

Emily

Thanks, Emily! That is definitely true. Nice presentation and graphics are essential to any effective budget engagement process, but if they aren’t complemented by actually taking the time and energy to get more people involved, and if citizens can’t easily figure out what the key takeaways are and give their input in a way that’s compiled and acted upon by public entities, then there is a real risk of turning people off the process.

I do think that companies like OpenGov and Socrata and Accela have taken the budget process a step forward with their financial visualizations, but there is a very real risk (one which is being borne out in more and more places, as I unfortunately discovered while serving as Balancing Act’s product manager) that local government managers and finance staff conflate them for real budget education, real budget feedback, and real engagement. In a perfect world, local governments would embrace a multitude of methods for getting people educated in and involved with one of the most important documents out there – the budget. This would include robust outreach to those who don’t usually show up to budget meetings, an ample presence on social media, complementing financial transparency tools with budget engagement and community ideation tools, and embracing a culture of innovation and creativity in all budget activities, perhaps in conjunction with local Code for America allies and entrepreneurs.

All this can be done with far less money and staff time than most elected and appointed officials think. I just wish there was more of an appetite for embracing some of these new technologies and merging them with the equally-important offline methods. Thankfully, some cities are taking the lead and serving as a shining example on this, like Boston, Philadelphia, Palo Alto, Salt Lake City, Paris, and others. I hope others will follow!

Kevin, Eric, and Emily –

This is a very thoughtful conversation, and I agree with most of what has been stated. Balancing Act, the online simulation to which Kevin refers to, was born because we (Engaged Public) spent years teaching public policy advocacy; which means that you MUST give future policymakers/advocates a strong foundation in governmental budgets (ideally before they are elected). Time and time again, we hear policymakers and elected officials try to explain budget realities to constituents, and both citizens and elected officials leave the room frustrated. Constituents either feel over or underwhelmed with the information presented and elected officials feel that the constituents can’t or are unwilling to understand the nuances, trade-offs, and complexities of budgeting.

Consider the Federal Budget that was just released on Balancing Act last week: http://www.federalbalancingact.com. Throughout the entire process, there was a push and pull with the subject matter experts at the Bipartisan Policy Center as to how much content and detail a user can digest. Some will say it’s too complicated, while others will say its too simple. However, given the tenor, tone of this election cycle — we think this tool is more important than ever. Thanks for the opportunity to comment.