It isn’t news that voters between the ages of 18-29 tend to turn-out for elections in substantially smaller numbers than other age groups in the population, and this has been especially true in mid-term elections. For example, in 2014 just 21% of voters in this age group voted. Thus, it was big news when data became available that young voter turn-out in the 2018 midterms was at 31%. This was the highest turnout in the last seven midterm elections.

My particular interest in the engagement of young people in the political process leads me to ask how we explain this increase and whether there are lessons civic educators can learn from this significant increase that might be replicated in future elections. There is no better source, in my view, than CIRCLE (The Center for Information and Research on Civil Learning and Engagement), for getting more detailed numbers and insight into youth voting.

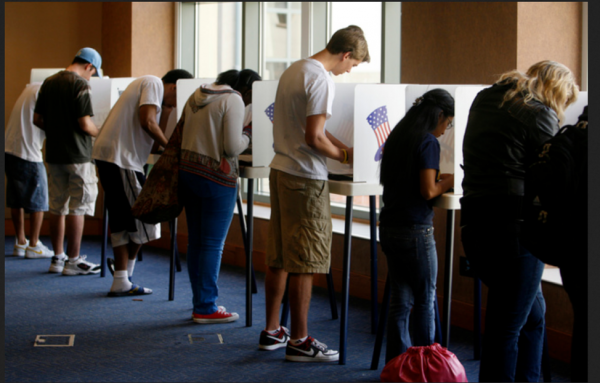

Understanding both who is mobilized to vote and how they are mobilized is information that can be helpful to political parties, local civic organizations, social science educators, and local governments. In discussing why youth voting matters, CIRCLE notes that “Voting is habit forming: when young people learn the voting process and vote they are more likely to do so when they are older…getting young people to vote early could be key to raising a new generation of voters.” CIRCLE also notes that the 18-29 year old cohort in this country outnumbers the group over the age of 65: there are 46 million young people eligible to vote and 39 million who fall into the “seniors” category. They also note that young people who are registered are very likely to vote – the key is getting them registered and providing them information about where and when to vote.

The increase in turnout among young voters in 2018 then, is likely explained, at least in part, by increased efforts to register and inform young people about the mid-term. The 2018 midterms were unusual in the amount of national attention focused on them, no doubt a consequence of the Trump presidency and the high levels of mobilization among both his supporters and those who dislike him. But beyond this, there is reason to believe that mobilization of young people also occurred because of concerted efforts by some organizations to get young people registered to vote.

Certainly, the most high profile of these efforts was the Parkland, FL high school students’ Road to Change project, which gained national media attention and took them around the country to encourage voter registration. Young voters in 2018 in Florida outperformed their peers across the country by meaningful margins. While the overall turnout nationwide for this age-group was 31%, in Florida it was 37%, a full 15% higher than it had been in the midterm of 2014. In certain local and congressional district races, there is no doubt this had an impact.

There have also been several national efforts to mobilize college students and measure the effects of such mobilization efforts. For example, the All In Campus Democracy Challenge is a nationwide effort to “change civic culture and institutionalize democratic engagement activities and programs on college campuses, making them a defining feature of campus life.” The Challenge collaborates with higher education institutions across the country to “[m]ake participation in local, state, and federal elections a social norm.” Wake Forest is a participating institution in the Challenge, and in 2018 it launched “Deacs Decide” as a program to raise awareness about the mid-term, get students registered to vote, and provide rides to the local voting place off campus.

Marianne Magjuka, director of the Pro Humanite Institute that sponsored the program, explained in an interview that part of the motivation for starting the “Deacs Decide” program came from data Wake received from another nationwide project on young voter engagement at Tufts University. The National Study of Learning, Voting, and Engagement has 1,150 participating campuses, divided fairly evenly among community colleges, 4 year public institutions, and 4 year private institutions. It provides participating campuses data on the voting behavior of their students. Magjuka said they were distressed to discover that Wake Forest students’ turnout fell below the national average among participating schools. In the 2014 midterm the turnout rate for Wake students was only 14.3%, while the average among NSLVE institutions was 19.1%. NSLVE hasn’t yet shared the 2018 data with participating schools but Magjuka is hopeful that the Deacs Decide program had some impact on turnout among Wake Forest students.

The data on voting participation by young people certainly shows room for improvement going forward. The All In Democracy Challenge encourages higher education institutions to set longer term goals that shape the culture and curriculum of schools. Wake Forest has developed an action plan through 2022 that includes developing an infrastructure for supporting this work year round (rather than just at election time) and partnering with Winston-Salem State and Salem College to move off of campus and into communities to encourage registration and voting among young people who don’t have the opportunity to participate in campus programs.

The biggest immediate barrier Magjuka and others working on young voter engagement see in accomplishing their goals is the new North Carolina Voter ID law. She says the law will be “challenging “ for higher education institutions in verifying residency and providing ID for college students who want to vote in the state. North Carolina Board of Elections has notified campuses about the steps that will be necessary for them to take in order for their students’ IDs to be accepted. “It’s unfortunate and shortsighted,” says Magjuka, “that rather than encouraging the new generation of citizens to engage with the political process, the legislature has erected hurdles to that engagement. Our job will be made more difficult but we remain committed to the work.”

Katy – nice summary with lots of data. Wondering about outreach to young people via community colleges. May be harder in some respects (no dorms or designated student housing) but important for inclusion across different family and work circumstances. Any thoughts to expanding in Winston-Salem beyond the three 4-year colleges you note?